A Makerspace is “a place where people can come together to use, and learn to use materials as well as develop creative projects” (Makerspaces Australia, n.d.). Makerspaces can be anywhere, but are commonly found in public and school libraries. It is best if the space “can be used for a range of activities with changing and flexible educational goals and creative purposes” (Makerspaces Australia, n.d.). Makerspaces and the idea of the maker movement are underpinned by pedagogies that focus on the learner as constructing their own knowledge through doing – through making. Sylvia Martinez tells us that “knowledge is born out of experience” (2014). If we give students the opportunity to use these Makerspaces to create something, then they are delving more deeply into what they are learning, rather than just taking notes, or listening to a teacher talk.

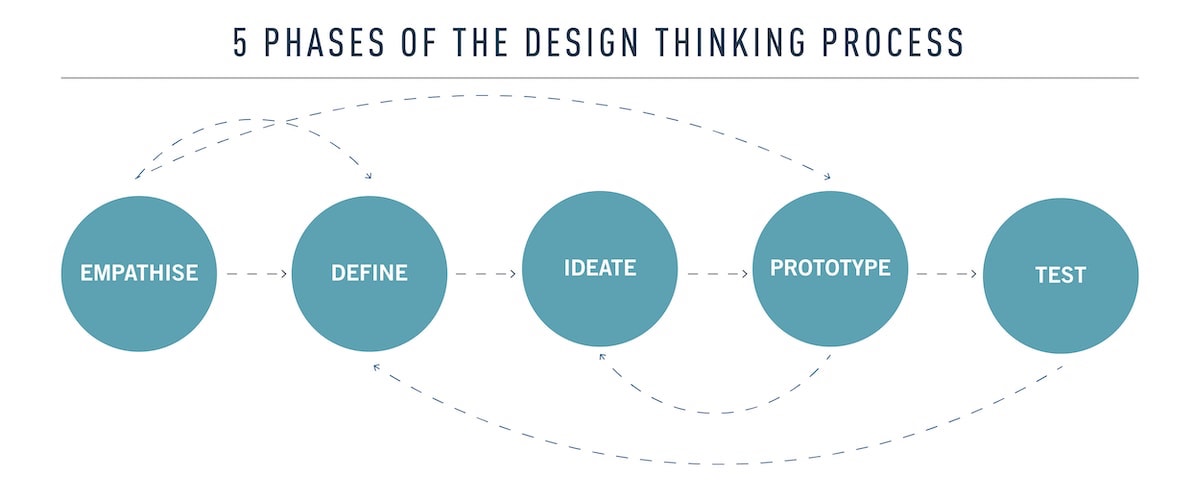

The main pedagogical theory that underpins Makerspaces is constructionism. Jonan Davidson talks about how constructionism is similar to constructivism in that it describes how people construct knowledge, but Papert added to the theory by arguing that learners also need to “construct real-world inventions which can be shared with others” (2014). If we allow our learners to use Makerspaces to engage in constructionist theory, then we are also enabling them to engage with content creatively and critically.

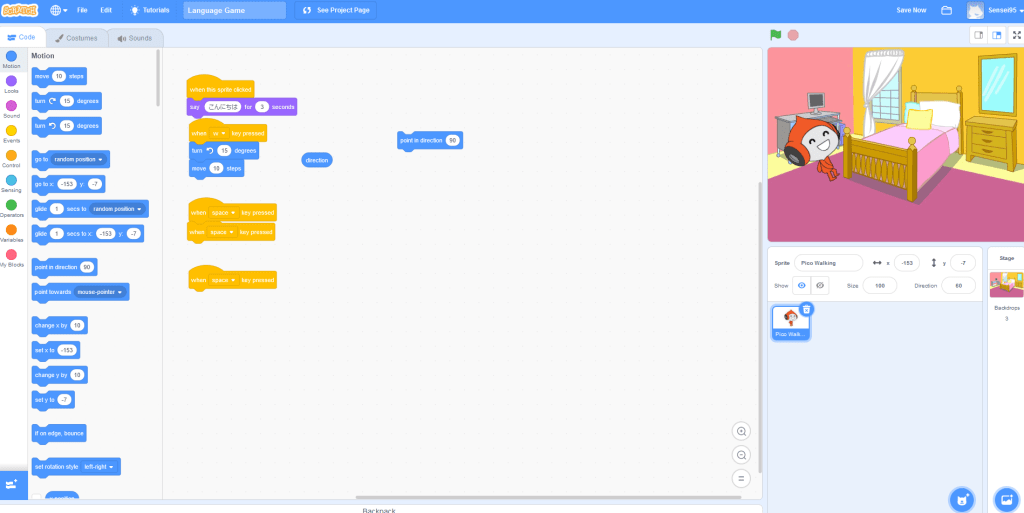

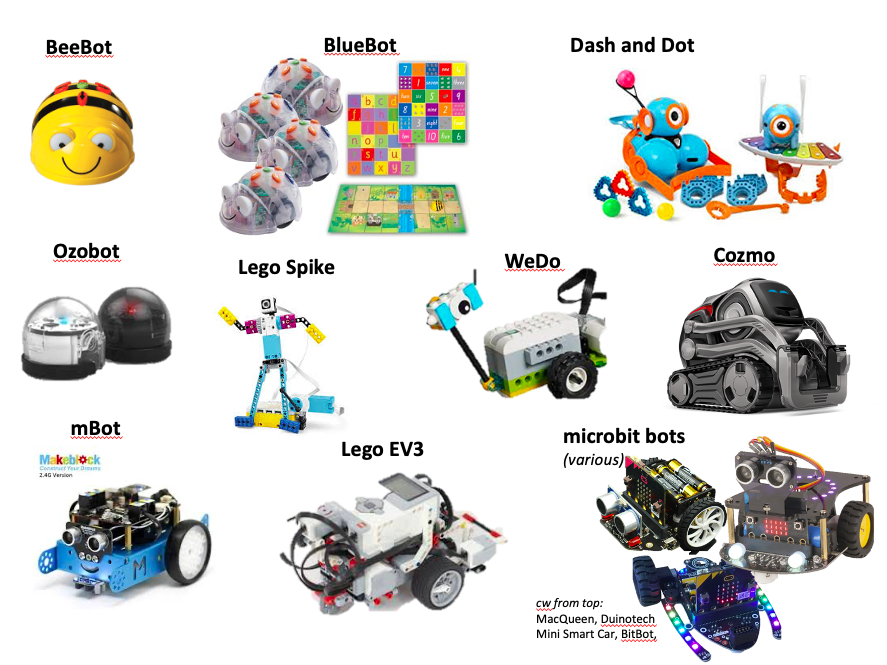

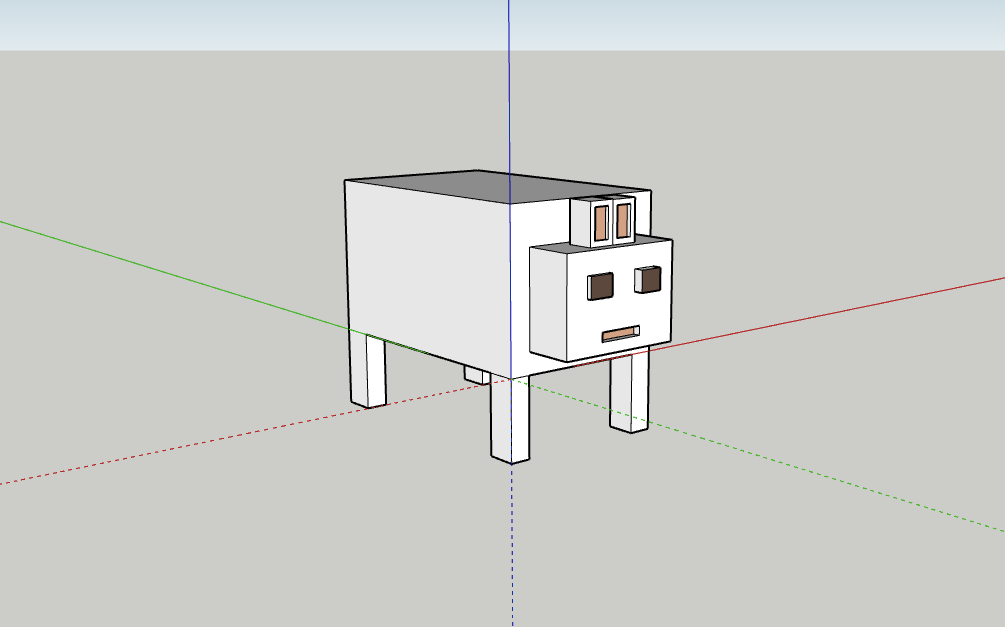

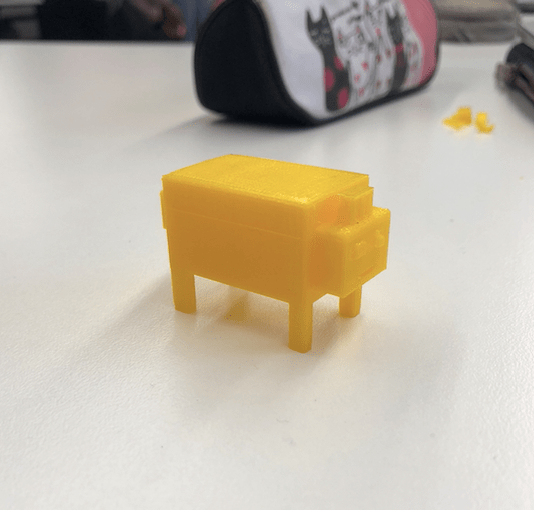

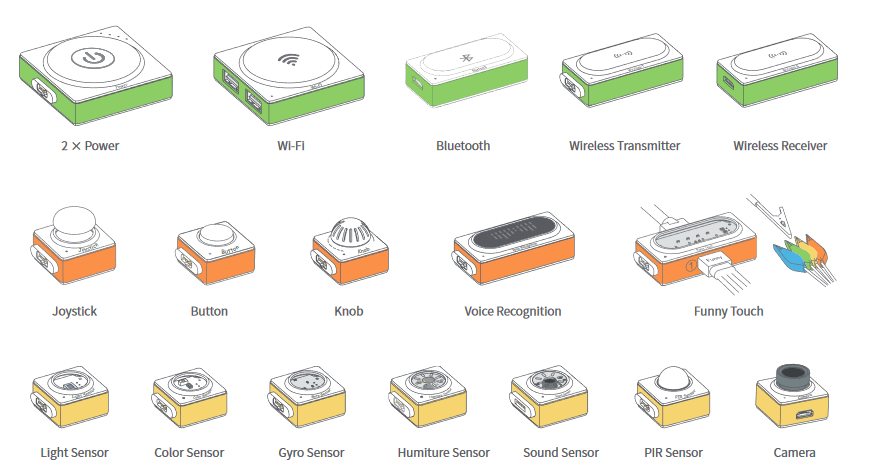

There are many different technologies out there that are appropriate for constructionist pedagogy and Makerspaces in particular. Today, I will be focusing on the Makeblock Neuron. The Neuron is a kit of programmable, magnetic blocks that have different inputs and outputs, resulting in a plethora of different functions and activities.

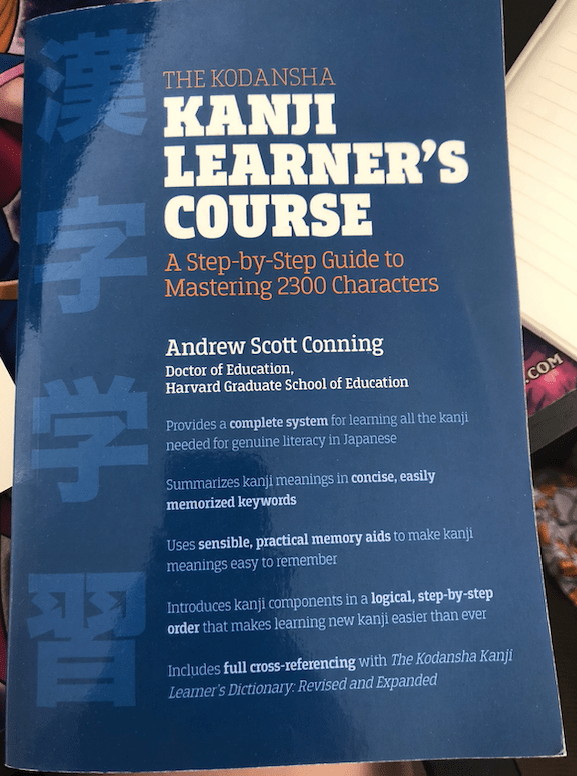

The Makeblock Neuron has uses in both primary and high school, and in all learning areas. The magnets and stability of the blocks make it good for younger students, while the programming aspects make it good for older students. Specifically for a languages/Japanese class, I would program the Neuron to respond to voice recognition with certain Japanese phrases, which would then be written in Japanese script on the display block, helping with vocabulary acquisition in the target language.

References:

Donaldson, J. (2014). The Maker Movement and the rebirth of Constructionism. Hybrid Pedagogy. Available at: https://hybridpedagogy.org/constructionism-reborn/

Makerspaces Australia. (n.d.). What is a Makerspace? Retrieved from http://makerspacesaustralia.weebly.com/what-is-a-makerspace.html

Martinez, S. (2014). Invent to learn: making, tinkering and engineering in the classroom [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDUHSPKvJRA